Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Depending on which side of the country you live on, you probably either hate or love sea urchins. Off the coast of California, there are too many of the spiny creatures. They’re destroying kelp beds, harming the entire ecosystem.

But off the coast of Florida—and throughout the Caribbean Sea—there aren’t enough urchins. And without them, coral reefs are dying off.

The ocean floor near Los Angeles is the largest graveyard for whales yet seen. Surveys have found evidence of more than 60 whale skeletons there. Scientists have used sonar and video cameras to map a couple of ocean basins that are centered about 15 miles offshore.

Researchers have been studying the region for years, in part because it was a dumping ground for DDT and related chemicals. Scientists are seeing how that affects life in the ocean, and how it might impact human health.

The image of more than a hundred thousand aircraft carriers floating through the air might sound like a scene from a Doctor Strange movie. But the weight of all those carriers equals the amount of carbon dioxide that humanity has pumped into the air every year over the past decade or so—11 billion tons per year. The carbon dioxide traps heat, warming the atmosphere.

The oceans help slow that process by absorbing about a quarter of the CO2 from the air, according to a recent report. More CO2 was being absorbed in parts of the North Atlantic and Southern Oceans.

When a hurricane or tropical storm rolls through, most birds fly around it, or find refuge in the calm “eye” at its center. But not the Desertas petrel. It can ride out the storm, then follow the system for days—all to catch an easy meal.

The petrel nests on a tiny, craggy island off the northwestern coast of Africa. There are only a few hundred of the birds, which are about the size of a pigeon. They’re strong fliers: every year they make a 7500-mile round-trip to the eastern North Atlantic Ocean.

The massive fire that engulfed Lahaina, on the Hawaiian island of Maui, killed more than a hundred people, and burned down more than 2200 buildings. And it had a much wider impact as well—on the offshore coral reef.

The fire roared to life on the morning of August 8th, 2023. Fueled by drought, low humidity, and strong winds, it destroyed much of Lahaina, displacing more than 10,000 people.

When beluga whales want to communicate with each other, they just use the ol’ melon—a blubber-filled structure on their forehead. Researchers have found that the whales intentionally change the shape of the melon. That may convey different emotions or intentions—whether they want to play, mate, or just hang out.

Belugas live in and around the Arctic Ocean. They have a thick layer of blubber to protect them from the cold. And they don’t have a fin on their back, which allows them to easily glide below the ice.

The most powerful undersea volcano ever recorded had an impact on our entire planet—from pole to pole, and all the way to outer space. And it may continue to impact parts of the world for years.

The Hunga Tonga volcano is in the southern Pacific Ocean, well east of Australia. It staged a massive eruption in January of 2022. It blasted more than two cubic miles of rock and ash into the sky, and created tsunamis all across the Pacific. Shock waves in the atmosphere raced around the planet for days.

One of the changes that goes along with aging is hair color. Red, blonde, black—regardless of the original color, our hair almost always turns gray or silver.

Fish don’t have hair, but many of them do change color as they age. They can take on different color schemes as they move through different stages of life.

Fish change color for many reasons. Some of the changes happen in a flash—a fish might blend into the background to protect itself from predators. Other changes are more gradual. A fish might change color when it switches gender, for example.

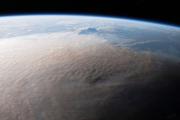

Some of the largest cities in Southeast Asia could be hit by bigger, badder tropical cyclones in the decades ahead. A recent study found that warmer seas and air could change where storms in the region form, how quickly they ramp up, and how long they hang around. The changes could be especially deadly for major cities along the coast.

Storms on the Sun can have both beautiful and annoying results. They create widespread displays of auroras—the northern and southern lights. But they can damage satellites, disrupt radio communications, and knock out power grids on the ground. They might even cause some whales to strand themselves.