Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

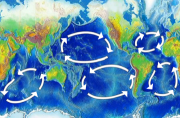

Much of the water in the world’s oceans is herded like cattle being driven to market—not by cowboys on horseback, but by strong currents. Known as gyres, they help control global temperatures and the nutrients available in different parts of the oceans. They also round up floating debris, forming giant garbage patches.

Green doughnuts are typically something you want to avoid. But some giant green doughnuts on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef may actually be good for us. They may store carbon on the ocean floor. That keeps it out of the atmosphere, where it would add to climate change.

You might want to save those leftover egg whites at breakfast. Researchers at Princeton University found a way to use them to filter salt and tiny bits of plastic from sea water. It’s a method that could be cheap and reliable, and could be used on a large scale.

The team was trying to mix up a new recipe for aerogel—a material that’s mostly air or other gas. It’s extremely light weight, but it’s versatile. It’s used for insulation, water filtration, and even to catch bits of comet dust.

If sharks had dentists, one might want to set up shop at Muirfield Seamount, near a set of islands in the Indian Ocean. A recent expedition there pulled up a haul of more than 750 shark teeth—the largest ever seen at a single site. Most of the teeth came from modern-day species. But a few belonged to the ancestors of megalodon, which died out millions of years ago.

Young killer whales off the coast of Washington and British Columbia like to nip at each other. That leaves white scars on their backs and sides—but they’re not permanent. That allows biologists to use the scars to learn about the life histories of these endangered animals.

They’re looking at southern resident killer whales—the smallest of the four types of resident killer whales. There are only 73 known members. They live in family groups, with the offspring staying with their mothers all their lives.

Marion Island is cold, windy, and remote—about half way between Antarctica and the southern tip of Africa. That makes it a great spot for studying the Southern Ocean—from the weather to the seas to the abundant life. In fact, a dozen or more hardy souls spend 13-month stretches doing just that.

Marion Island is owned by South Africa. It’s the peak of a volcano, which last erupted in 2004. It measures about 10 miles wide by 15 miles long.

Sea birds face all kinds of threats these days: a warmer climate, decreasing food supplies, attacks by invasive species, and others. One of the most basic is rising sea level, which threatens to cover some of their nesting grounds. To help species survive, conservationists are relocating sea bird chicks to higher ground.

An example is the Tristram’s storm petrel. It breeds in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. But it was wiped out on the island of Midway by rats, and it’s threatened by plastic pollution on other islands in the chain.

The Chengjiang formation in China is one of the world’s most important fossil sites. It’s not that big—it covers a couple of square miles in Yunnan province, in the southwestern corner of the country. But it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and an International Geological Heritage Site. That’s because the location has yielded some of the earliest fossils of complex life on Earth—more than 500 million years old. That includes what may be the oldest fish yet seen.

Blue crabs live their entire lives in the water. That’s where they eat, breed, and even breathe. So, some marine scientists were a bit astonished when they saw blue crabs popping out of muddy pits on shore to grab fiddler crabs.

Blue crabs are found all along the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, on the bottoms of shallow bays and estuaries. They have been seen to dart out of the water to grab prey, but only by a few feet.

Marine scientists need all the help they can get. Exploring the oceans is hard and expensive. In recent years, though, they’ve gotten help from some special research assistants: marine mammals. They attach small cameras or instruments to seals, whales, and other animals. Their journeys tell us a lot about ocean conditions, ocean life, and the animals themselves.