Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

A massive tsunami in northwestern Sumatra wiped out coastal villages for miles. Only one survived. But by a century later, its influence began to wane -- the result of a new power settling on the sites of the destroyed villages.

Archaeologists began studying the area in detail after another tsunami, in 2004, killed more than 150,000 in Sumatra alone. And in 2006, one researcher discovered bits of pottery and Muslim gravestones that were uncovered by the 2004 tsunami. He recruited a large team to study a 25-mile stretch of coastline in a region known as Aceh.

For the flashlight fish, school doesn't end at night. In fact, the schooling is just getting started. The fish is one of the few known to congregate in schools at night, even when there's no moonlight. That's because the flashlight fish brings its own lights, so all the members of the group can keep an eye on each other.

The flashlight fish is found at depths of up to a few hundred feet in the tropical Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. It has a patch below each eye that emits blue light. It's one of the few species of light-producing fish that doesn't live in the deep ocean.

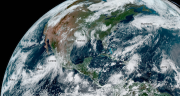

When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in 2017, it killed almost 70 people and inflicted more than a hundred billion dollars’ worth of damage.

Not all of the damage was visible, though. Some of it was on the bottom of the lagoons along the coast. Harvey ripped up seagrass beds, which provide shelter and breeding grounds for many species of fish and shellfish, and hunting grounds for birds and other critters. That could change the complexion of those regions for years.

With a top speed of a few hundred feet per hour, the giant tortoise won’t win many races. Compared to some of the longest waves in the oceans, though, it’s like an Indy race car. The waves are almost entirely below the surface. And they can take a decade or longer to ripple from one side of an ocean to the other. Until recently, that made them almost impossible to see.

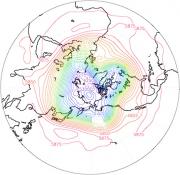

Earth's changing climate is expected to produce higher temperatures and stronger tropical storms. And when you put those two together, the results could be especially deadly.

A team of scientists recently studied the risks of extreme heat -- defined as a heat index of 105 degrees Fahrenheit or higher -- after the landfall of a hurricane or typhoon. The team found that such a one-two punch could pose major health risks for millions of people.

For more than three months, giant kelp off the coast of California bobbed up and down like a pumpjack in an oil field. The goal of that motion was to replace a few pumpjacks by developing a replacement for some of the country’s oil.

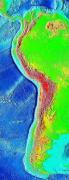

The Pacific coast of South America is a bit like a medieval castle surrounded by a moat. The “castle” is the Andes Mountains, which hug the coast. And the “moat” is the Peru-Chile Trench -- a gash in the ocean floor that’s miles deep.

Castle and moat were built by the motions of two of the plates that make up Earth’s crust. The Nazca Plate, which makes up part of the floor of the Pacific Ocean, is sliding under the South American Plate, which makes up most of the continent.

The Mediterranean Sea has been recording sea level for millions of years in a cave on a Spanish island. As the water rises and falls, it adds layers of minerals to rock formations inside the cave. And interpreting those layers may help scientists better understand what could happen to future sea level.

There are many symbols of love, from the heart to red roses. And for some couples in Japan, it’s a glass vase -- the skeleton of a sponge.

Venus’s flower basket is a type of glass sponge. Various species of glass sponge are found around the world, usually in fairly deep waters. The largest concentrations of them form reefs off the coast of British Columbia.

Today, the word “trade” means to swap something. That hasn’t always been the case, though. Centuries ago, it meant a path or a track. The new definition blew in on the wind -- the trade wind.

Trade winds blow in belts that flank the equator. The Sun heats the air and oceans at the equator. Warm, humid air then rises and heads toward the poles. As it reaches about 30 degrees north and south of the equator, the air cools and descends.