Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

We humans have been known to eat some pungent foods, from boiled cabbage to brussels sprouts to limburger-and-onion sandwiches. But a mollusk that lives in the mud at the bottom of a Philippine lagoon tops them all. It gets by on hydrogen sulfide -- a nasty gas that smells like rotten eggs. Or to be more precise, bacteria that live in its gills consume the hydrogen sulfide and convert it to a more palatable form.

Many marine creatures hang out in beds of seagrass or kelp to hide from predators or prey. But the leafy seadragon beats them all. It’s covered with leafy appendages that make it look like a bit of kelp. And it floats along with the currents just like the kelp, so it’s hard for either prey or predator to pick it out.

The heart of a typical adult human can pump about 2,000 gallons of blood per day. But that’s anemic compared to the pumping capacity of a sponge -- the living kind, not the kind you use to wash off your kitchen cabinets. The amount of water it pumps can be up to 20,000 times the volume of its own body. For a good-sized sponge, that can be almost 20,000 gallons a day.

James Bond, Indiana Jones, and other action heroes can’t seem to avoid waterfalls. They plummet down them, or they just miss them, narrowly avoiding a gruesome fate.

But no hero has taken the plunge down the world’s tallest waterfall -- and probably won’t anytime soon. That’s because it’s under water -- a two-mile drop between Greenland and Iceland.

When sea otters decided to move into Glacier Bay in Alaska, they didn’t mess around. They first appeared in the bay in the 1990s -- more than two centuries after they’d been hunted to near extinction. But by the time of the most recent census, in 2012, the population had soared to more than 8,000 -- an increase of more than 40 percent per year.

One of the most geologically active regions on Earth is at the western edge of the Pacific Ocean, along a chain of volcanic mountains both above and below the ocean surface. The Mariana Arc includes more than 60 underwater volcanoes, known as seamounts. And scientists have seen big changes along that arc in recent years.

The activity is caused by the motions of two of the plates that make up Earth’s crust. One plate is plunging below the other. The intersection between them has created the deepest spot in the oceans, a canyon known as the Mariana Trench.

If Marvel Comics needs a character to star in yet another TV show, here’s a suggestion: Iron Snail. It would be protected from villains by an iron shell, and by iron plates around its “squishy” bits.

Nature has already created the prototype for Iron Snail: an inch-long snail found around hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean. It’s called the scaly-foot snail for the armor that covers its foot -- the fleshy part that extends out of the shell.

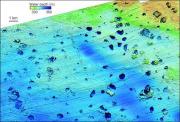

As the last Ice Age came to an end, big bubbles of gas on the floor of the Barents Sea popped like champagne corks. That left hundreds of craters -- some of them up to two-thirds of a mile across.

Geologists discovered the crater field in the 1990s. It’s about a thousand feet deep in a region north of Norway. The scientists suggested the craters were produced by retreating glaciers. But they didn’t have the tools to study the region in detail.

Big fish that move fast could lose a bit of their swagger in the coming decades. Warmer ocean waters will provide less oxygen, which could reduce the maximum size of some species of fish -- especially those that are the most active.

Researchers have noticed that some species are already getting smaller -- species like herring, sole, and haddock. In part, that could be the result of overfishing -- the bigger fish get caught, leaving the smaller ones behind. But a recent study suggests that warmer oceans could also be playing a role.

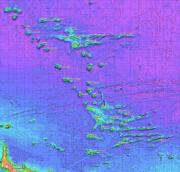

In the summer of 2017, a research expedition took a good look at a string of underwater mountains north of Hawaii. Scientists used sonar to map the volcanic mountains, known as seamounts, which formed tens of millions of years ago. And they found a profusion of life on and around the mountains -- corals, jellyfish, sea stars, sea spiders, and a bright red sea toad. They’ll be studying the findings for years.