Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Treating a headache with a torpedo may sound like overkill, but that’s just what happened in ancient Greece and Rome. Of course, the torpedo wasn’t a projectile like that fired from modern submarines. Instead, it was a type of fish -- a ray that can deliver a powerful electric charge.

Torpedo rays are found in shallow coastal waters around the world. The Atlantic torpedo lives along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the United States, and the Pacific torpedo is found from Baja California to British Columbia.

The rise in global temperatures isn’t smooth and even, like turning on a flame under a tea kettle. That’s because it’s a complicated process that involves the atmosphere, the oceans, and other factors.

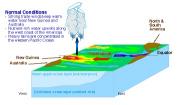

One of those factors seems to be trade winds over the Pacific Ocean. Weaker winds lead to higher temperatures, while stronger winds tend to cool things down a bit.

When a whale dies, its carcass is a massive buffet for bottom-dwelling organisms. They can strip the bones bare in a matter of months. But the feast doesn’t end there. Tiny worms feed on the bones themselves, carpeting the skeleton in what looks like a giant feather boa.

The first of these bone worms were discovered in 2002, a couple of miles deep off the coast of California. Another dozen or so species have been found since then, in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

For much of the United States, El Niño is a welcome event. It tends to bring more moderate temperatures to most of the country, and more rainfall to parts of the southwest. It also reduces the number and intensity of tropical storms that hit our coastline. And recent research suggests another benefit: fewer tornadoes and big hail storms across most of the country.

El Niño occurs every few years, when the surface of the eastern Pacific Ocean gets warmer than average. More water evaporates and streams across the U.S., altering weather patterns over millions of square miles.

One of the best ways for biologists to learn about marine life is to tag along for the ride -- to plunge into the ocean depths, or travel on a migration that may cover thousands of miles. Since it’s hard to know how many sandwiches to pack for such a trip, though, scientists use proxies: satellite trackers, video cameras, and other devices.

Many adventurers yearn to “sail the seven seas” -- to ply all the world’s oceans. Well, we have a little bad news for those folks. There aren’t seven oceans. In fact, there’s only one -- the global ocean.

Modern-day maps typically show five oceans: the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, and Arctic, plus the recently designated Southern Ocean. All but the Southern Ocean are at least partially bounded by the continents or by strings of islands, which makes them look like separate bodies of water -- but they’re not.

Some people keep their nose to the grindstone, their ear to the ground, or their eye on the ball. But the roseate spoonbill keeps its bill in the muck. The beautiful bird feeds by sticking its wide, spoon-shaped bill into murky waters and sweeping it from side to side. The inside of the bill is lined with sensitive detectors that feel the vibrations of small fish, shrimp, insects, or other possible prey. When it feels one of these tasty morsels, the bird snaps its bill shut, then uses the bill to separate the good bits from the mud and debris.

Don’t tell anyone else, but we know where you can find a fortune in gold -- about 20 million tons of it. It’s in the oceans. Not in sunken pirate ships or Spanish galleons, but dissolved in the water itself.

In fact, ocean water is like a well-stocked chemical warehouse. About three-and-a-half-percent of it consists of molecules of something other than H-2-O.

Getting to know all the fish in the seas is a tough job. There’s a lot of ocean to cover, after all, and many species aren’t especially easy to find -- they have limited numbers or range, or they lurk in waters that aren’t often explored.

An example is the frilled shark. It looks almost nothing like most other shark species. Its body is long and sinuous, like an eel’s, and its head looks more like a snake than a fish. It has a prehistoric look, which is appropriate, since its ancestors were around at least 80 million years ago.

A few years back, McDonald’s tried a change in the way it packaged its burgers. They were separated to keep the hot ingredients hot and the cold ingredients cold. And there seems to be a similar separation in the oceans. The warm upper layers seem to be getting warmer than thought, while the cold lower layers don’t seem to be getting any warmer at all.

About 90 percent of the extra heat created by global warming goes into the oceans. But tracking just where that heat is going is a tough job.