Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

The chilly waters that separate the northern coasts of Alaska and Siberia are some of the liveliest in the world. They teem with everything from algae to polar bears. Yet life there is changing in a hurry. And scientists are paying close attention.

The region is known as the Chukchi Sea. It covers an area as big as Texas. Most of its shallow waters support abundant life, including some of the world’s largest populations of polar bears, Pacific walruses, and other marine mammals.

Two of the best-known symbols of Northern California are fog and the giant redwood tree. During summer, in fact, they’re often seen together. But a recent study suggests that their relationship isn’t as close as it used to be.

Redwoods inhabit a narrow strip along California’s Pacific Coast, from near the Oregon border to south of San Francisco. They can grow as tall as a 30-story building, and live for centuries.

A century after the Vikings began colonizing Iceland, life there was desperate. An Icelandic saga recorded that crops failed, creating a famine. The old and helpless were killed and their bodies thrown over cliffs, and the survivors were forced to eat anything they could catch, no matter how unappetizing.

The woes were caused by a drastic change in climate. And the shells of long-dead molluscs have revealed just how drastic.

In some ways, the nautilus is like its cousins, the squid and octopus. It uses tentacles to pull in its prey and a sharp beak to rip it apart, and it’s jet propelled. But in another way, it’s more like a submarine. It has a hard shell that protects it and allows it to move up and down in the water.

The nautilus lives in the tropical waters of the western Pacific Ocean. It can grow up to several inches long, and live 15 years or longer.

In the spring of 2006, a whirling current stirred up the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of France. It forced water from the surface all the way to the bottom, a mile and a half deep. The water most likely carried a lot of tiny shrimp, jellyfish, bacteria, and other creatures -- many of which lit up the depths with their own light.

Marine biologists watched it happen with instruments attached to one of the world’s oddest astronomical telescopes: a thousand light detectors anchored to the bottom of the Mediterranean.

If a species of octopus found off the coast of Indonesia had a good agent, it might get a lot of gigs on late-night talk shows. That’s because it’s one of the best mimics in nature -- it can imitate everything from a snake to a jellyfish. The imitations might not be good enough to win any acting awards, but they are good enough to keep the octopus safe from predators.

The mimic octopus was discovered in 1998. It spans a couple of feet from armtip to armtip, and it lives in shallow, muddy waters off the mouths of rivers.

Five and a half million years ago, the Mediterranean Sea was little more than a giant hole in the ground. Cut off from the Atlantic by a rock wall across the Strait of Gibraltar, it dried up. The little water that remained was so salty that almost nothing could live in it, and its surface was perhaps a mile or more below the level of the Atlantic.

But soon after that, things began to change. A recent study says the Mediterranean refilled first with a trickle, then with one of the greatest floods our planet has ever produced.

Over the last decade, marine scientists have been busily counting the organisms in the oceans. And not surprisingly, they just don’t have enough fingers and toes to add them all up. They’ve already announced thousands of possible new species, and should add many more to the list when they report on the Census of Marine Life this fall.

The list of possible new species includes jellyfish, sponges, shrimp, crabs, and many others. One example is a relative of the jellyfish known as a comb jelly.

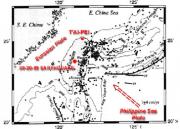

It’s hard to think of a typhoon as a life-saver. In the western Pacific, these giant storms kill thousands every year, and cause billions of dollars in damage. Yet in Taiwan, they may actually save lives: Research shows they may help prevent monster earthquakes.

“Typhoon” is just another name for a hurricane. It’s a giant tropical storm that can pack strong winds, heavy rains, and a massive storm surge -- not something you want to mess with.

The Arctic tern doesn’t look like a marathon winner. The bird is about a foot long and weighs just a few ounces. Yet this little dynamo spends a third of each year trekking between the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle -- a twisting round-trip of almost 45,000 miles. That’s by far the longest known migration path of any bird.

The Arctic tern breeds at high northern latitudes -- from Alaska and Canada to Greenland, Scandinavia, and Siberia. When the northern summer draws to a close, though, it heads south.